Jack-in-the-Pulpit series by Georgia O'Keeffe still startles our imagination and even today we create our own interpretations that are superimposed onto the artist's own interpretation of her work. She began these paintings as a relatively unknown woman artist at a time when no one else was creating this type of work. With these paintings she wanted to find a way to become noticed. She was right, people took notice. Everyone becomes an instant armchair psychiatrist, creating narratives for O’Keeffe, and her paintings. Narratives of repression, and longing. Even the man she would marry, Alfred Stieglitz, teased out these narratives. At times he would display her flower abstractions along with intimate photos he had taken of O’Keeffe. During his life, Stieglitz was an outspoken champion of modern art. His words held weight in the art world then as they do today.

How Georgia Okeeffe felt about the flower

“I hate flowers - I paint them because they're cheaper than models and they don't move.”

“I realized that were I to paint flowers small, no one would look at them because I was unknown. So I thought I'll make them big, like the huge buildings going up. People will be startled; they'll have to look at them - and they did.” - Georgia O’Keeffe

Behind the Start of Jack in the Pulpit Series

The Jack-in-the-Pulpit series is the last major set of flower paintings that O’Keeffe created at Lake George. The Stieglitz family owned property at this upstate New York lake. Georgia, and Alfred would summer there with his extended family. It was the summer of 1930, and O’Keeffe was already feeling the pull to New Mexico. In 1929, she traveled, and worked in Santa Fe, and Taos for several months. There were signs of wear in her marriage. She was beginning a slow shift to western landscapes and vistas. Lake George had always belonged to Stieglitz, and his family. New Mexico belonged to O’Keeffe’s family.

Where were the Jack-in-the Pulpits Growing?

O’Keeffe spotted a small patch of Jack-in-the-Pulpits near her studio. She was inspired, and painted six canvases in total. They were important enough for her to keep five of the canvases for the rest of her life. She bequeathed them to The National Gallery of Art.

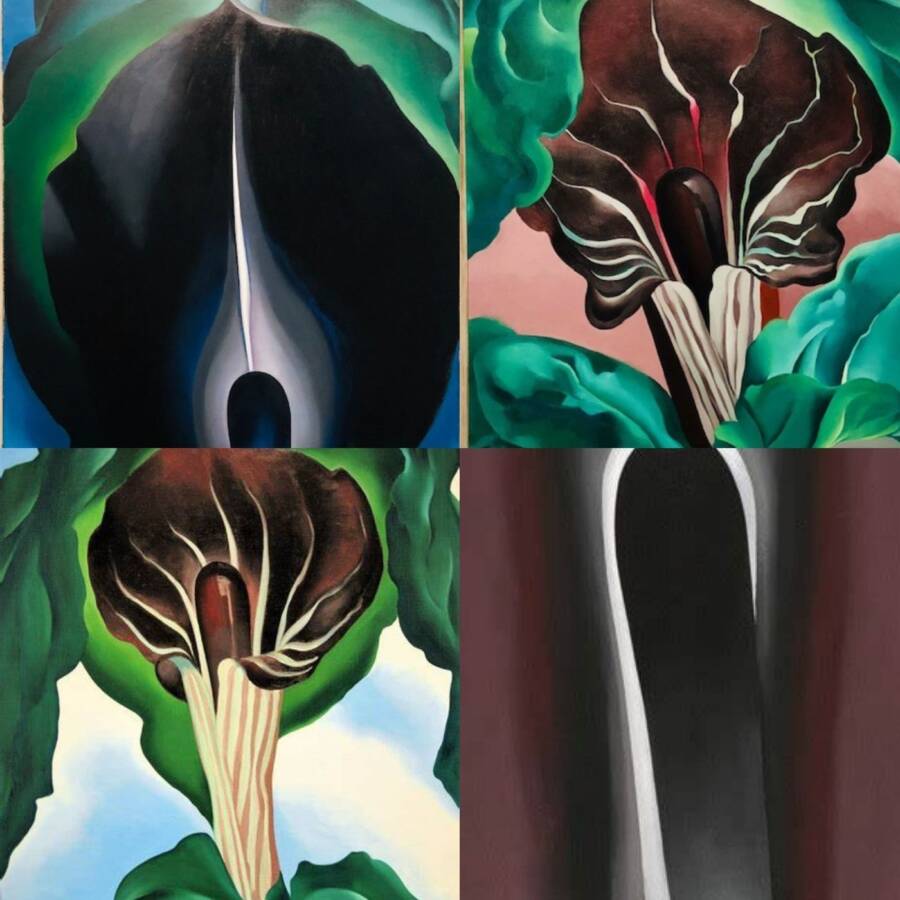

The Progression of the Series

The series follows the flower from reality to abstraction. “Jack-in-the-Pulpit No. I” fills the entire canvas. It is the closest to a botanist’s rendering of the flower. The colors are natural, the features are clear. This is the painting she did not keep. Maybe her thoughts on realism hold the answer....

“Nothing is less real than realism. Details are confusing. It is only by selection, by elimination, by emphasis, that we get at the real meaning of things.”

It is these three words, selection, elimination, and emphasis, that can give insight into why O’Keeffe kept these works, and not the other painting.

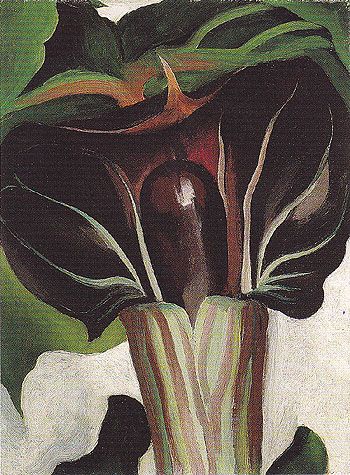

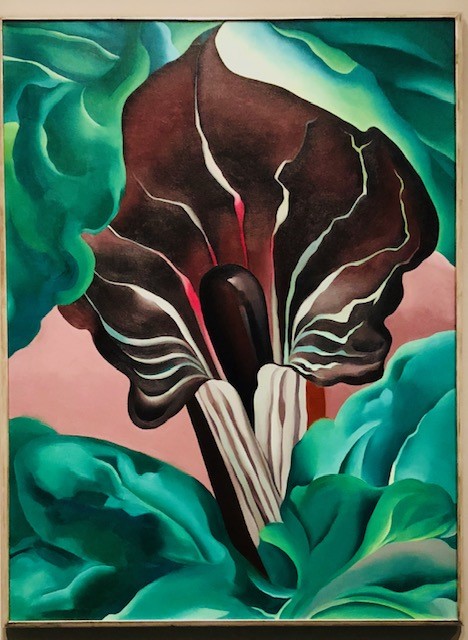

“Jack-in-the-Pulpit No. II”, and “Jack-in-the-Pulpit No. III” have an emphasis on color. The canvases still have roots in realism. The design of both images is very similar. In each a lone flower sits mid canvas. O’Keeffe presents her subject like Botticelli’s Venus rising from the sea. Instead of a seashell, O’Keeffe frames her subjects with a spray of leaves. In “No. II,” the background is earth, In “No. III” it is sky. O’Keeffe’s color scheme is now intense and unnatural.

In “Jack-in-the-Pulpit No. IV”, and “Jack-in-the-Pulpit Abstraction - No. V” O’Keeffe keeps the vibrancy she has built, but begins to eliminate details. She hones in on her subject. The flower fills the painting, spilling off the sides. Sky, and leaves, are pushed to the painting’s edges. These are obviously still flowers, but it is harder to tell what type of flower you are viewing.

By “Jack-in-the-Pulpit No. VI” O’Keeffe has created something new. There are hints of blue, and red baked into the black and brown landscape, but these purplish hues are all that is left of the vibrant colors found in the previous works. The painting is an extreme close-up of the stamen. It is now so large that the flower has disappeared. The painting becomes whatever the viewer wishes it to be.

We are back to a Rorschach test of sorts. What does the viewer see, and what does that say about them? O’Keeffe, like a magician, carefully curated every piece of herself that she shared with the world. Almost all photographs of her, even the ones taken by Stieglitz are in black and white. People who knew her described her wardrobe to be equally monochrome. When her Santa Fe home, now a museum, is viewed, it echoes the minimalistic approach to her New Mexico paintings. O”Keeffe, the woman, disappeared. It is her art that she spoke through.

Yet she understood that once the art is let loose into the world it becomes a part of the viewer’s experience too. That is all right. Just take care to remember your interpretation might not fit with other peoples.

“I made you take time to look at what I saw and when you took time to really notice my flower, you hung all your associations with flowers on my flower and you write about my flower as if I think and see what you think and see — and I don’t” — Georgia O’Keeffe.